In the last instalment in this series on jihād, I reflected on my youthful opposition to all religion, Islam included, a product of shallow reading and groundless certainty. This post continues my attempt to undo that habit, and help others do the same, by restoring Qur’ānic verses to their historical and textual context.

Following the Qur’ān’s two periods of revelation as traditionally defined—the Meccan and Medinan period—I explored how the Meccan verses stressed patience, endurance, and nonviolent resistance, even amidst severe persecution. Drawing on classical Islamic sources (mainly different “tafsīrs,” Qur’ān commentaries, and the “Sīrah Rasūl Allāh,” the oldest biography of the Prophet’s life), I showed how jihād in this difficult period denoted a moral and spiritual striving, rather than warfare, and how the virtue of sabr, patient endurance, stood at the epicentre.

In today’s instalment, I turn to the Qur’ān’s Medinan verses, in which divine permission for armed struggle was finally given, and restrictions for it were laid down.

Out of respect for my readers’ attention span, the “verse of the sword” will be discussed in a separate instalment.

The Hijra

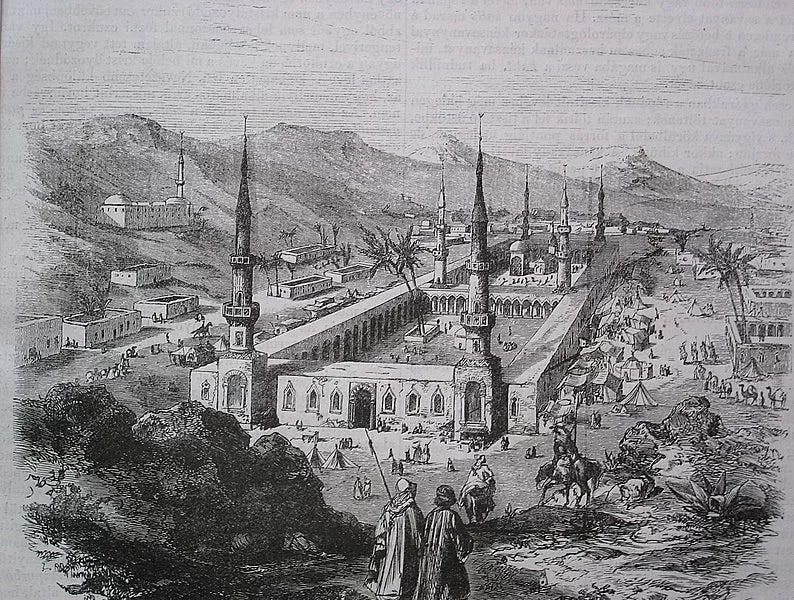

In Mecca, the Prophet’s message of absolute monotheism had begun to unsettle the power structures, provoking increasingly severe persecution by the city’s polytheist elite. Thus, in 622 CE, the Prophet’s followers migrated to Yathrib (later to be known as Medina). After a failed assassination, the Prophet also departed the city, joining his followers in Yathrib.1

This migration—the Hijra, which marks the beginning of the Islamic calendar—was a cardinal moment in early Islamic history. The Prophet’s role shifted from preacher to statesman, and the Qur’ān’s tone progressively changed. The early believers were no longer a small, marginal group: they were now a nascent political community in a society that was not only tribally fractured, but that also had strongly established religious communities whose favour they had to win.

The Religious Communities of Medina

Unlike Mecca, Medina was home not only to a small Christian community, but also to a sizeable Jewish one.2 While the Prophet's message gained traction among some of Medina’s Arab tribes, the Jewish community did not accept Muhammad’s claim to prophethood. This set the stage for a tense, ambivalent relationship.

In response to this, a covenant was drafted at the Prophet’s insistence. This was later known as the Constitution of Medina.3 Its purpose was to come to an agreement among the city’s different groups, which were:

the Mu’minūn (literally, “the believers” or “those who grant security”), which included the Prophet’s Meccan followers and eight groups belonging to the two main Arab tribes in Medina;

the Yahūd, the Jews involved in the agreement;

and the Muslimūn, who were either associated with, or part of, a Jewish group known as the Yahūd Banī ‘Awf.4

For the Jews who entered this pact, the document promises aid, equal rights, and protection.5

But the agreement is not entirely clear in its terms, and much depends on how we interpret a single Arabic word. In most readings, Mu’minūn and Muslimūn are declared an umma (a community, or “group of mutual legal solidarity”). This has led to two possible interpretations: either the Jewish signatories formed a separate umma living alongside the Muslims, or they were part of the same umma.6

Strangely, the three main Jewish tribes of Medina—the Banū Nadīr, Banū Qurayza and Banū Qaynuqā‘—are not mentioned in the document. This suggests that only a small part of the Jewish community participated.7 But it also presents a problem: when relations between the Prophet Muhammad and the Jewish tribes later broke down—leading to the expulsion of the Banū Nadīr and Banū Qaynuqā‘, and the attack on the Banū Qurayza—it remains unclear not what went wrong, but which pact it was that they had breached.8

When Fighting Became Permitted

The change from nonviolent to violent resistance didn’t happen immediately. At first, the verses of the Medinan period ordered the believers not to fight, but rather, to focus on their duties of prayer and almsgiving (e.g. Q. 4:77 and 2:109).9

But the clashes with the Quraysh continued,10 and about two years after the migration, the Muslims were officially granted divine permission to take up arms. In Sūrah al-Hajj, we read:

Permission [to fight] is granted to those who have been attacked, because they have been wronged… (Q. 22:39).

This verse marks an important shift. For the first time, Muslims were allowed to resort to violence. However, the use of the passive voice, “those who have been attacked” (yuqātalūna), should not be overlooked: this permission to fight was (and is), for many scholars, limited to self-defence.11

The verse that follows clarifies who was considered in that case to have been wronged:

… those who have been driven unjustly from their homes, only for saying, ‘Our Lord is God.’ (Q. 22:40)

The Qur’ān thus identifies the injustice to be the forced displacement and persecution of the believers because of their devotion to monotheism. Defending faith, and the freedom to practice it, is therefore deemed a just cause for war against the polytheists.

After this, another justification for armed resistance is given:

[...] if God did not repel some people by means of others, many monasteries, churches, synagogues, and mosques, where God’s name is much invoked, would have been destroyed (Q. 22:40).

Here, resistance is cast not just as self-preservation, but as preservation of the sacred. This verse is striking in its inclusivity. It describes armed resistance as a means to protect the sacred houses of Jews, Christians, and Muslims alike. One could infer from it that Muslims should defend adherents of other monotheistic faiths when these are targeted by polytheists (as does, for example, the scholar Asma Afsaruddin).12

But the permission comes with a caveat. The passage concludes by describing the kinds of people God favours:

God is sure to help those who help His cause–God is strong and mighty–those who, when We establish them in the land, keep up the prayer, pay the prescribed alms, command what is right, and forbids what is wrong: God controls the outcome of all events (Q. 22:40).

In other words, God’s help is conditional. He will only support those who, once they have become established, continue to uphold their religious duties and behave morally. Only if they preserve this moral and spiritual integrity will they be successful in their resistance.13

Thus, these verses formulate a distinctly nuanced and restricted understanding of when violence is justified.14 They provide permission, but not licence. Still, as I will show, the restrictions are not unambiguous, making it challenging to pin down what exactly is permitted and not permitted.15

The Qur’ān’s Rules for Engagement

It’s also worth looking at verses 190-5 of Sūrah 2, which concern the conduct and goal of martial jihād. These would later become the foundation for the ethics of warfare in Islamic law.16 To provide a broader picture, I’ll begin by quoting these verses in full:

Fight in God’s cause against those who fight you, but do not overstep the limits: God does not love those who overstep the limits.190

Kill them wherever you encounter them, and drive them out from where they drove you out, for fitna is more serious than killing.17 Do not fight them at the Sacred Mosque unless they fight you there. If they do fight you, kill them – this is what such disbelievers deserve – 191

but if they stop, then God is most forgiving and merciful.192

Fight them until there is no more fitna, and dīn is devoted to God (yakūna dīn li’Llāh). If they cease, there can be no (further) hostility, except towards aggressors.193

A sacred month for a sacred month: violation of sanctity (calls for) fair retribution. So if anyone commits aggression against you, attack him as he attacked you, but be mindful of God, and know that He is with those who are mindful of Him.194

Spend in God's cause: do not contribute to your destruction with your own hands, but do good, for God loves those who do good.195

Verse 190 lays down various restrictions on armed conflict. Some scholars interpret it as a prohibition on offensive warfare.18 Others see it as a ban only on transgression, meaning that Muslims must not harm non-combatants such as women, children, the elderly, clergy, the disabled, or those uninvolved in hostilities.19

Either way, proportionality is essential: the response must be measured, not brutal.

But what about “kill them wherever you encounter them”? This verse, quoted in isolation, may sound like it calls for an indiscriminate hunting down and slaughtering of unbelievers. But if we consult the commentaries, we can see that this is not the case.

According to the exegete Fakhr al-Dīn al-Rāzī (d. 1209), for example, it is a response to the early Muslims’ concern as to whether they could retaliate if attacked within sacred areas or during hajj. Even if attacked in these circumstances, it is saying, they are permitted to retaliate, even lethally.20

The same logic is extended in verse 2:194: if enemies violate the sacred months by initiating violence, Muslims may respond in kind.

Then comes a charged word: fitna. In verse 2:191, it’s presented as a justification for fighting: “Fitna is worse than killing.” But what does fitna mean? It depends on whom you ask. The word itself has a wide semantic field: trial, charm, temptation, persecution, tribulation, disorder.21 And so, translators seem to interpret it based on what they believe the source of such trial, charm, temptation, persecution, tribulation or disorder to be.

Some translators, like Dawood, equate it with idolatry.22 Others, like Hilali and Khān, stretch it further to mean rejection of Islam, suggesting that disbelief itself justifies war. In their rendering, fitna includes “polytheism, to disbelieve after one has believed in Allāh,”23 such that the “trial or temptation of associating partners with the one God” is worse than killing.24

But if fitna is taken to mean persecution, as in Haleem, Khattab and Arberry’s translations, or oppression, as in Asad’s, then it is the oppression or persecution of Muslims that is considered worse than the killing of polytheists.25

In verse 2:193, the Qur’ān states the aim of this struggle:

Fight them until there is no more fitna, and worship is devoted to God (yakūna dīn li’Llāh).

Again, it is the interpretation of fitna that determines the end-point of fighting. Haleem believes it to be the ceasing of persecution. In line with this, he interprets yakūna dīn li’Llāh (the meaning of “dīn” including both worship and religion) as referring specifically to worship in the Sacred Mosque, now to be dedicated to God in peace.26 By contrast, Hilali and Khān understand it to be the ceasing of the polytheists’ disbelief, so that all worship in general is dedicated to God.27

Thus, the ambiguity of words like dīn and fitna makes them into Rorschach tests. Radically different interpretations of these verses, and therefore of the goal to be achieved by fighting, are spawned. Where one sees defensive struggle against persecution, another sees a call for warfare until conversion.

“Do not contribute to your destruction”

Lastly, verse 195 adds another rule for the conduct of martial jihād, one that is often interpreted by contemporary Muslims as prohibiting suicide:

Spend in God's cause: do not contribute to your destruction with your own hands, but do good, for God loves those who do good.

This warning against self-inflicted ruin has also been interpreted in different ways. For the authors of the Tafsīr al-Jalālayn, it is about spending for the sake of God, not withholding funds or avoiding the struggle. For them, “contributing to your destruction” refers to abandoning the military jihād or withholding monetary support for it, as this puts the enemy at an advantage.28

But whom does it refer to? According a source cited by al-Wāhidī, it refers specifically to the Ansār (the “Helpers,” those who helped the Prophet and his followers in Medina), who had initially been generous in giving alms but had ceased, possibly due to drought.29

In the Tanwīr al-Miqbās, one finds a rather different interpretation. For its author, the verse is about the Companions (i.e. followers) of the Prophet who were on their way to perform the lesser pilgrimage (the ʿumra). It addresses spending not for the martial jihād, but for inner jihād in the form of pilgrimage.30

Across these commentaries, however, the core idea is that contributing to your destruction refers to failing to act, whether by withholding monetary or military support, or neglecting one’s worship. It is a warning against communal or spiritual negligence.

As for the view that this verse prohibits taking one’s life, I was unable to find any classical tafsīrs affirming this interpretation. It seems to find far stronger support in verse 29 of Sūrah al-Nisāʾ (“Do not kill yourselves, indeed God is merciful towards you” (Q. 4:29)). Given the limits of my research, however, I cannot address this issue in more detail here.

Challenges of Interpretation

In reading the verses that first permitted armed resistance, we encounter significant nuance and restraint, but also ambiguity and interpretive variance. The polysemy of words like fitna, and the elliptical style of the Qur’ān (that is, its tendency to omit words within sentences), produces drastically different interpretations, explaining how the same sacred text can inspire both the most peaceful and the most militant of believers.

Given this, I wonder: what responsibilities do we bear in our reading of scriptures?

Some tentative suggestions: for me, studying these varying interpretations has been a reminder that sacred texts can never speak for themselves. They cannot correct us when we deviate from their intended meaning, or when we distort that meaning through our own desires, intentions and assumptions. All we have are our own fallible minds’ interpretations, as do those who criticise our understanding. Our subjectivity, it seems to me, is inescapable.

Perhaps the challenge, then, is not simply to determine what the text means, or has meant to interpreters of the past, but to approach it with some self-reflectiveness, acknowledging that our interpretations may reveal as much about ourselves as they do about the text—or more. For often we read not as listeners in search of understanding, but as defenders in search of proof, or as adversaries in search of the fatal flaws we assume are there. Can these approaches really yield the truth?

Perhaps, instead, we should see these texts not just as genuine revelations—or, for those who do not believe in them but are nevertheless curious, as cultural artefacts worthy of closer study—but as looking-glasses for our own selves.

Some things to think about:

Do you agree or disagree with what I just said?

What does it mean to “misinterpret” a sacred text?

If a text can yield multiple or contradictory interpretations, is that a flaw in the reader or in the text (or is there another way of looking at this)?

Can respect or reverence coexist with a critical spirit? If so, how can one reconcile them?

If you have thoughts on any of these, I would love to hear your perspective in the comments. Vehement disagreement is welcome too.

Our next instalment will, finally, turn to the Qur’ān's most pivotal Medinan verses on jihād. In particular, we’ll take a close look at the so-called “Sword Verse,” as well as at the hermeneutic principle of abrogation, which is indispensable for understanding the Qur'ān (or rather, for understanding how it has been interpreted). With the help of classical commentaries, we’ll explore the circumstances of revelation in order to illuminate the verses’ intended meaning and scope of application.

Starting with the upcoming instalment, new posts will be released a few times a month, rather than every Sunday.

Notes for curious or informed readers

To ensure readability in this series, most transliteration marks are omitted from Arabic terms, except where necessary for clarity (ū, ā and ī are retained; ḥ, ṣ and others are not).

Abū ʿAbd Allāh Ibn Ishāq, Sīrat Rasūlillāh [Life of the messenger of God], trans. Alfred Guillaume (Oxford University Press, 1955), 324.

Reuven Firestone, “The Qur’an on Jews and Judaism,” in CCAR Journal: The Reform Jewish Quarterly (2018), 163.

However, as historian Michael Lecker notes, the term “constitution” is not quite correct, one reason being that the document mainly addresses tribal issues, as well as warfare, blood money, ransoming and war expenses. Michael Lecker, “The Constitution of Medina,” in Encyclopaedia of Islam, Three, ed. Kate Fleet et al. (Brill, 2007): 100.

Ibid., 100.

Ibid., 102.

Lecker offers another view: the word might not be umma at all, but a-m-na, meaning “those who are secure.” If so, it would suggest that the covenant promised protection to the Yahūd Banī ‘Awf and the other Jewish groups granted the same rights, rather than integrating them into a single religious community. Ibid.

Ibid., 101.

Farhana binti Ideris and Öznur Özdemir, “Understanding Muslim - Jewish Relationship in Medina during the Era of Prophet Muhammad,” Journal of Sirah Studies 11 (2021): 94.

Muhammad A. S. Haleem, “Qur’anic ‘Jihād’: A Linguistic and Contextual Analysis,” Journal of Qurʾanic Studies 12 (2010): 149.

Here it must be mentioned that, while the Quraysh did persist in their attacks in Medina, the biographical literature also details the Prophet’s, or his followers’, multiple raids on Qurashi caravans, which began soon after the migration to Medina. Therefore, it is not entirely clear who antagonised whom. See Ibn Ishāq, Sīrat, 281, 285286, 360-362, 445–447 (inter alia).

See Asma Afsaruddin, Striving in the Path of God: Jihad and Martyrdom in Islamic Thought (Oxford University Press, 2013), 307.

However, not all exegetes agree. Some, like the seminal 10th-century exegete Ibn Jarīr al-Tabarī, read the same word as active (yuqātilūna, those who fight), and downplay the distinction. For him, in battle, it hardly matters who was the attacker: both sides are equally combatants.

Ibn Jarīr al-Tabarī, Tafsīr al-Tabarī [The Commentary of al-Tabarī], vol. 5, ed. Bashar A. al-Harshani (Al-Resala Foundation, 1994), 321.

Asma Afsaruddin, “Jihad in Islamic Thought,” in The Cambridge World History of Violence, vol. 2, ed. Matthew S. Gordon, Richard W. Kaeuper & Harriet Zurndorfer (Cambridge University Press, 2020): 452.

Haleem, “Qur’anic ‘Jihād’,” 150.

See ibid. Haleem also notes that verses 190-5 of sūrah 2 contain four prohibitions, seven restrictions, and multiple cautions, such as “be mindful of God,” “God does not love those who overstep the limits,” and “do not contribute to your destruction with your own hands.” Ibid., 152.

As Landau-Tasseron notes, it is impossible to distil a coherent doctrine of warfare from the Qur’ān without reference to the exegetical tradition, and its rulings regarding warfare often contradict each other or lend themselves to multiple interpretations. Ella Landau-Tasseron, “Jihād,” in Encyclopaedia of the Qur’ān, vol. 3, ed. Jane D. McAuliffe et al. (Brill, 2003): 38.

See Afsaruddin, Striving, 43.

To preserve the polysemy of certain words, I will leave them untranslated until they are explained. The alterations are my own.

See Afsaruddin, “Jihad,” 457.

Landau-Tasseron, “Jihād,” 39. The latter view is held, for example, by the exegete al-Rāzī, who understands the verse to prohibit fighting non-combatants. Fakhr al-Dīn Al-Rāzī: Tafsīr al-Fakhr al-Rāzī [The Exegesis of Fakhr al-Rāzī], part 5 (Dār al-fikr, 1994), 138.

Ibid., 140. However, in Ibn Kathīr’s commentary, the opposite interpretation for Q. 9:5 is offered: due to the prohibition of offensive combat in the Sacred Mosque (Q. 2:191), attacking the polytheists wherever one finds them means on the earth in general, but not in the Sacred Area. Abū al-Fidāʾ Ibn Kathīr, Tafsīr al-Qurʾān al-ʿAzīm [The Commentary of the Magnificent Qurʾān], ed. Sāmī b. Muhammad al-Salāma, vol. 4 (Dār Tayba, 1999), 111.

The Oxford Dictionary of Islam, ed. John L. Esposito (Oxford University Press Inc, 2004), 87 / Reuven Firestone, Jihād: The Origin of Holy War in Islam (Oxford University Press, 1999), 85.

The Koran, trans. Nessim J. Dawood, rev. ed. (Penguin Classics, 2014).

The Noble Qur’an, trans. Muhammad T. al-Hilali, & Muhammad M. Khān, 2011 ed. (King Fahd Complex, 1998), 40, note [1].

Firestone, Jihād, 85.

The Message of the Qur’an, trans. Muhammad Asad (Dār al-Andalūs Limited, 1980) / The Koran Interpreted, trans. Arthur J. Arberry, 2 vols. (Macmillan, 1955) / The Clear Qur’an, trans. Mustafa Khattab (Book Of Signs Foundation, 2016).

The Qur’an, trans. M. A. S. Abdel Haleem (Oxford University Press, 2004).

The Noble Qur’an.

Tafsir al-Jalalayn, trans. Feras Hamza. Royal Aal al-Bayt Institute for Islamic Thought, 2021). Retrieved from Altafsir.com.

Asbāb al-Nuzūl [Circumstances of Revelation], trans. Mokrane Guezzou (Royal Aal Al-Bayt Institute for Islamic Thought, 2008). Retrieved from Altafsir.com.

Tanwīr al-Miqbās [Illumination of the Source], trans. Mokrane Guezzou (Royal Aal Al-Bayt Institute for Islamic Thought, 2007). Retrieved from Altafsir.com.