In the last instalment, “When Jihād Became Permitted,” I turned to the Qur’ān’s Medinan verses: those revealed after the Prophet’s emigration to Medina. In contrast to the Meccan period, when nonviolence and patient endurance were valorised, the Medinan period saw the believers first being granted divine permission to take up arms. But the terms were cautious and conditional.

In Sūrah 22:39–40, the first verses to permit fighting, violence is described as a response to persecution, with a striking emphasis on protecting freedom of worship for all monotheists. This self-restraint is echoed in Sūrah 2:190–4, which lay down restrictions on warfare, such as proportionality and moral conduct.

At the end, I turned my attention to Sūrah 2:195—“do not contribute to your own destruction”—with a brief look at how it was interpreted in some classical exegeses (i.e., commentaries). While the verse is often taken today as a categorical rejection of suicide, these commentaries focus, instead, on the dangers of passivity, and contextualise the verse in different ways.

Taken together, these verses formulate a nuanced, restrained approach to warfare, though much hinges on the interpretation of certain ambiguous terms, like fitna and dīn. And so, it’s worth asking: to what extent are these terms like Rorschach tests, telling us something about the psychology of the reader, rather than about the verse’s intended meaning?

Some verses in the Qur’ān sound harsh when read in isolation. They speak not of tolerance, patience and religious freedom, but of death and punishment. Verse five in Sūrah al-Tawba—often called “the sword verse” in both classical exegesis and modern discourse, despite the “sword” not once being used in the Qur’ān—is one of them.

If you don’t know what I mean, here it is:

When the sacred months are over, kill the polytheists wherever you find them. Capture them, besiege them, lie in wait for them at every ambush. But if they repent, establish prayer, and give the alms, let them go their way. God is forgiving and merciful.

Read like this, the verse seems to demand a conversion-or-death approach: a radical departure from the previous policy of non-aggression and religious freedom. Indeed, some claim it calls for the fighting of polytheists until death or repentance,1 and it is frequently quoted (often simply as “kill the polytheists wherever you find them”) to prove that Islam advocates for violence against non-believers. Others say that it’s a specific wartime order, not a command valid for all time.2

What are we to make of such starkly different readings, and of a verse that seems to upend everything that came before it?

As always, we need to start with the verse’s setting.

Why Kill the Polytheists?

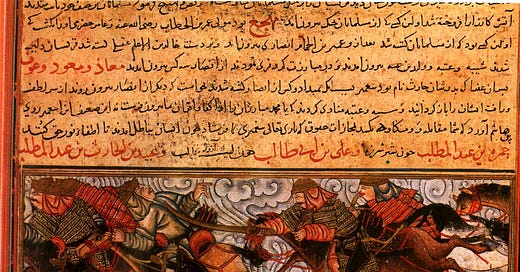

The verse appears in Sūrah al-Tawba (“The Repentance”), which was revealed towards the end of the Prophet Muhammad’s life. It opens by announcing the end of a treaty following certain polytheists’ violation of it, followed by four months in which they can move freely.

To understand this, it’s important to know that at the time of its revelation, there were four kinds of polytheists in Medina:

– Those with fixed-term treaties, who did not break their terms;

– Those with open-ended ones, that is, treaties without fixed terms;

– Those with whom the Prophet had concluded the Hudaybiyya peace treaty in 628 CE;

– And those with whom he had concluded no peace treaties.3

The verse in question says:

When the sacred months are over, kill the polytheists wherever you find them. Capture them, besiege them, lie in wait for them at every ambush. But if they repent, establish prayer, and give the alms, let them go their way. God is forgiving and merciful. (Q. 9:5)

On the surface, this verse seems to call for unrestricted war against polytheists qua polytheists. Once again, however, context matters.

The surrounding verses tell us not only about certain polytheists’ violation of a treaty (verses 8, 10 and 12), but also that they had attacked the believers first, slandered their religion, and schemed to drive out the Prophet (verses 12 and 13). It is the polytheists’ aggression that justifies fighting against them, not their unbelief.

There is a continued concern with faithfulness to treaties. Verse four, for example, states that peaceful and non-aggressive polytheists were not to be fought. If they upheld their agreements and did not aid enemies, the believers were to honour their treaties with them until the end of their term. Verse seven says that if the polytheists were true to the believers, the believers were to be true to them.

So, even without the more specific context and interpretation found in commentaries, the surrounding verses seem to belie the notion that the Qur’ān treats disbelief alone as a valid reason for warfare. The verses themselves repeatedly offer different justifications, none of which are “disbelief” or “idolatry.”

You might be asking yourself: why, then, is this verse so often interpreted as commanding the indiscriminate fighting of polytheists, until their death or conversion, simply because of their unbelief?

Hopefully, by the end of this piece, it will be clearer why this reading was, and continues to be, persuasive to some Muslims, while it is rejected so vehemently by others.

Which Polytheists?

Views on this differ. Some scholars, both classical and modern, have argued that the verse targets only those who broke their agreements, not polytheists in general. This is supported by the preceding verse, which emphasises that those polytheists who honoured their agreements are exempt.

More specifically, some scholars link this verse to the Quraysh, who had been persecuting the believers in Mecca, and had violated the Hudaybiyya treaty by supporting Banū Bakr, their ally, in an attack against Khuzāʿah, the ally of the Prophet, such as Ibn Kathīr and the authors of the Tafsīr al-Jalālayn.4

The Tafsīr al-Jalālayn explains the verse by saying that the polytheists who violated their treaty should be killed, whether inside or outside a sacred place, taken captive, and confined in castles and fortresses. But if they repent from idolatry, observe the five daily prayers, and pay the poor-due, they should be left alone.5

This may sound like it’s about forced conversion. However, the authors’ commentary on the following verse provides crucial clarification: if a polytheist seeks safety to learn about Islam, they must be granted protection and escorted to a safe place, even if they reject the faith.6 So while the end-point seems to be the conversion of polytheists who had violated their pacts, it is not a conversion under threat of death.

This interpretation can also be found in the Tanwīr al-miqbas, as well as the exegeses of al-Tabarī, al-Wāhidī, and al-Zamakhsharī.7

The exegete Fakhr al-Dīn al-Rāzī goes in a slightly different direction. Firstly, he offers a different context, linking the verse to a question asked ‘Alī, the Prophet’s cousin and later fourth caliph. A polytheist had inquired whether someone approaching the Prophet after the grace period would be killed. ‘Alī reportedly answered by reciting the sword verse.

Al-Rāzī also reads a more timeless principle into the verse, namely that mere imitation of precedent is insufficient in religion; true reflection and consideration of the proofs are needed. If it were not so, he argues, the polytheist would not have been offered respite in order to hear the Qur’ān, but rather, commanded to profess belief in God or die. Instead, polytheists should be granted safe conduct, so that they can accept Islam after having considered its proofs—or reject it.8

These commentaries suggest that the verse mandates violent confrontation only with those polytheists who violated their treaties, not all polytheists. Even then, the aim does not seem to be forced conversion. Faith, if it comes, must come freely, in line with the important dictum: “There is no compulsion in religion” (Q. 2:256).

But not all scholars agree with the reading of these exegetes. And the source of this disagreement is, at least partly, the application of a single hermeneutic principle: the principle of naskh.

The Impact of Naskh

Which verse speaks the final word?

In a nutshell, the principle of naskh, meaning “abrogation”, asserts that later verses may supersede earlier ones when their rulings conflict. This steered the extra-Qur’ānic discourse on jihād in a direction that diverged radically from the Qur’ān’s early peace-keeping spirit. The “sword verse” was later declared to annul any calls for patience, forgiveness, or peaceful coexistence.

Since the Qur’ān neither refers to naskh explicitly, nor formulates a clear principle for it, nor specifies which verses were abrogated, it was left to the scholars to decide.

On the pro-naskh side, Ibn Kathīr, a medieval exegete, cites the early authority al-Dahhāk ibn Muzāhim as saying that verse five abrogated every treaty between the Prophet and any polytheist. Ibn Kathīr adds that, according to Ibn ʿAbbās, the Prophet’s cousin, no polytheist was ever granted a treaty or promise of safety after its revelation.9

The Tafsīr al-Jalālayn also attributes to Ibn ʿAbbās the view that it abrogated multiple peaceful verses, including Q. 8:61 (“But if they incline towards peace, you must also incline towards it […]”)10 and Q. 4:90 (“[…] so if they refrain from fighting you and offer you peace, then Allāh does not permit you to harm them”).11

By contrast, neither al-Wāhidī nor al-Zamakhsharī read verse 5 as abrogating earlier verses. According to Asma Afsaruddin, it was only after al-Tabarī that the pro-abrogation line of interpretation appears to have become predominant.12 Increasingly, scholars invoked this principle to justify their more militant readings.

As Afsaruddin notes, the enduring divide between peaceful and militant groups rests on this interpretive disagreement. Were we to read the Qur’ān as a whole—taking all its verses into consideration even if they appear, at first sight, to contradict earlier ones—we would have to interpret verse five in light of the earlier prohibition of offensive warfare in Q. 2:190, not as overriding it.13 Therefore, the importance this principle has in later discourse on jihād can’t be overstated.

How should the Qur’ān be engaged with?

The debate also raises broader questions about how one should engage with the Qur’ān. In Afsaruddin’s words:

Should the Qur’an holistically engaged remain the final arbiter and source of Muslim ethical and legal deliberations or must its text be mediated—even truncated—by exegeses that defer to specific historical circumstances for the political and material gain of particular Muslims?14

Going into this more deeply, or into more recent scholarly approaches to abrogation, would take us too far afield. The key point is that later understandings of the martial jihād, including its legal principles, depended partly on an extra-Qur’ānic concept, not on the text alone.

(To be clear, I am not suggesting that abrogation is non-Qur’ānic, just that the principle was inferred from certain verses, rather than being explicitly formulated in it.)

The Qur’ān does not offer a set of clear-cut rules for warfare. It does not tell us which rulings, if any, are no longer valid, which are universal and which context-specific. This ambiguity makes it difficult, and perhaps impossible, to distill a doctrine of war from it without relying on later elaborations.15

And yet, this does not make relying on commentaries a neutral, hazardless solution. Commentators brought assumptions to the text that may or may not reflect the Qur’ān’s original meaning. Moreover, as Afsaruddin suggests, these assumptions may have served other purposes than truth-seeking alone.

What seems clear to me is that human interpretation is always fraught with contingencies. It is up to us to decide what to make of them, whether we want to perpetuate the same thinking or embark on new paths of understanding.

Some things to think about:

How can we recognise when scriptural interpretation serves political or personal ends?

How can one make sense of (apparent) contradictions in the Qur’ān without introducing tools or concepts that are not (explicitly) mentioned in it?

To what extent is the principle of abrogation a necessary tool for understanding the Qur’ān?

If you have thoughts on any of these, I would love to hear your perspective in the comments!

In the next instalment, I’ll turn to another verse from Sūrah 9, sometimes referred to as the “jizya verse.” This one addresses not polytheists, but Jews and Christians, and has also been granted abrogating status by some scholars. What position does it take towards non-Muslims, and what exactly is its scope of application?

Notes for curious or informed readers

To ensure readability in this series, most transliteration marks are omitted from Arabic terms, except where necessary for clarity (ū, ā and ī are retained; ḥ, ṣ and others are not).

See Christopher J. van der Krogt, “Jihād without apologetics,” Islam and Christian-Muslim Relations 21 (2010): 132.

See Muhammad A. S. Haleem, “Qur’anic ‘Jihād’: A Linguistic and Contextual Analysis,” Journal of Qurʾanic Studies 12 (2010): 152.

Niaz A. Shah, “The Use of Force under Islamic Law,” The European Journal of International Law 24 (2013): 348.

Jalāl ad-Dīn al-Mahallī & Jalāl ad-Dīn al-Suyūtī, Tafsīr al-Jalālayn [Commentary of the two Jalals], trans. Feras Hamza (Royal Aal al-Bayt Institute for Islamic Thought, 2008), 166.

Al-Mahallī & al-Suyūtī, Tafsīr, 165. “Then, when the sacred months have passed — that is, [at] the end of the period of deferment—slay the idolaters wherever you find them, be it during a lawful [period] or a sacred [one], and take them, captive, and confine them, to castles and forts, until they have no choice except [being put to] death or [acceptance of] Islam.”

Ibid., 165.

For an overview, see Asma Afsaruddin, Striving in the Path of God: Jihad and Martyrdom in Islamic Thought (Oxford University Press, 2013), 88.

Fakhr al-Dīn al-Rāzī, Tafsīr al-Fakhr al-Rāzī [The Exegesis of Fakhr al-Rāzī], part 15 (Dār al-fikr, 1994), 236-237.

Abū al-Fidā’ ibn Kathīr, Tafsīr al-Qurʾān al-ʿazīm [The Commentary of the Magnificent Qur’ān], ed. Sāmī ibn Muhammad al-Salāma, vol. 4 (Dār Tayba, 1999), 112.

Al-Mahallī & al-Suyūtī, Tafsīr, 162-3.

Ibid., 85.

Afsaruddin, Striving, 58.

Ibid., 297.

Ibid.

See Ella Landau-Tasseron, “Jihād,” in Encyclopaedia of the Qur’ān, vol. 3, ed. Jane D. McAuliffe et al. (Brill, 2003): 38.